Apple and Accessibility

May 18, 2017

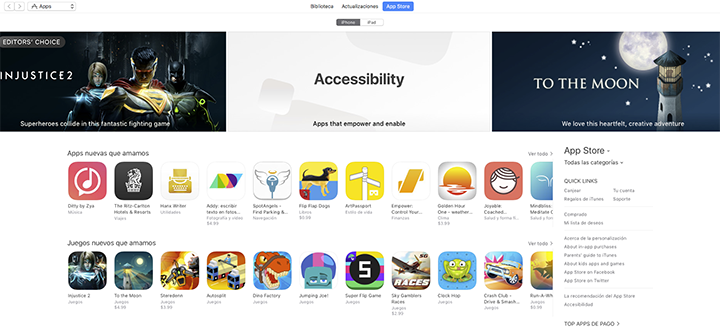

It’s Global Accessibility Awareness Day and this week I’ve seen a great deal of coverage regarding accessibility (or “a11y” as you will sometimes see it) as it pertains to Apple. It was featured front and center in the iTunes App Store:

Tim discussed accessibility with activists. Mashable wrote a great article on Apple’s dedication to accessible technologies. And it also received high praise from John Gruber at Daring Fireball:

"Apple’s commitment to accessibility is one of my very favorite things about the company. It’s not just the right thing to do for people who truly need these features — it makes the products better for everyone."

It’s true, the work that Apple has done with accessibility is second to none and companies like Microsoft and Google could learn a lot by following Apple’s lead in this area. When you look at available accessible technologies with companies like Microsoft, they seem primitive in comparison. Apple deserves the recognition for the work that they are doing to change the lives of people through their technologies.

I need the reader to accept two truths before the next part of this article: first, accessibility is never going to be a numbers game. Everyone has their tips for life enhancements through accessibility features ( 1 2 3 ), but these are accessibility-as-customization and not the intended purpose of the features. So even if a particular accessibility feature gains traction by preference or culture, that’s not what I’m talking about. Next, as Gruber points out, it needs to be for everyone.

If you can accept these two arguments, then I hope you will get something out of the rest of this article. I don’t have a lot of experience with all of Apple’s assistive technologies, but I do have a lot of experience with one: Speak Screen. Speak Screen is the text-to-speech (TTS) technology that, when enabled, reads through the content on your screen element-by-element, line-by-line. When it works, it’s an example of the intuitive, world-changing technology that only Apple could create. It’s the type of technology that makes the technology-part fall away and the relationship between the user and the content becomes seamless. For those that rely on this, this is Apple at its best. When it doesn’t work the experience can be jarring, especially if you’re using a poorly written app, like The Atlantic’s iOS app (great content, awful app) or Le Monde (video below). There are ways to do this right, and if a publisher can’t afford to maintain an app, content could still be accessible through the web, where Apple and Safari take care of navigating the accessibility tree. Apple provides guidelines on accessibility in apps and there are some developers who do it perfectly, like The New Yorker Today and The New York Times.

Here is an example of everything working as it should:

Just as Apple provides the tools and frameworks for creating first-class, accessible apps, they also provide a wide array of high-quality text-to-speech voices for turning text into words. This is a practice that started when Apple licensed the Nuance RealSpeak voices in Lion and iOS 5. Famously, this included the voice known as ‘Samantha’, later known as Siri. All the voices are named after people one might associate with the region: Nora for Norwegian, Satu for Finnish, Diego for Spanish of Argentina, Moira from Ireland.

Steve Jobs on stage presenting Apple 10.7, Lion.

By packaging these high-quality voices with iOS and OS X (later ‘macOS’), Jobs was liberating the world from an era when text-to-speech sounded like the semi-concussed Norwegians described by Douglas Adams. Before this, it was practically impossible for people to gain access to these voices. Microsoft has a compatible backend, SAPI, but they only ship with awful-sounding voices. Linux has Festival 😬. If you’ve ever taken a look at trying to purchase these voices, you know that they have complex licensing agreements, that obscure the actual cost and create an additional barrier. Apple annihilated that barrier and made it as easy as a tap of a button. But the release cadence was always OS X first, then iOS. You could download high quality voices in any language on OS X years before you could do the same thing on iOS and I like to think that accessibility was a major selling point on maintaining these licenses. The benefits to users can hardly be over-stated: if you are interested in a new book, Nora can narrate with ease. If you are reading the morning news, Diego can give you the scoop. And if you’re chatting on Slack, Moira can do her best impersonation of Sara (though it’s still pretty Moira, if I’m being honest). With each release since Lion, if you had TTS voices installed, you noticed that Apple and Nuance continue to improve these voices and this technology. This is a trajectory that culminated in 2014, with the advent of iOS 8, when the world got Screen Speak. We had the technology to effortlessly interact audibly with the written word through artfully crafted, crystal-clear voices. Or at least we did for some people.

The problem is that while this technology works for the monolingual populations of the world, it has never worked for bilingual populations. Imagine Montreal, where French and English co-exist seamlessly. Consider Barcelona, where Catalan may enjoy prestige over the official language, Spanish. Think about the massive number of bilingual populations around the world. If you are bilingual and you have any reason at all to use Speak Screen, you are going to have to make a difficult choice:

Left, French read by Karen (Austrailian English). Right, English read by Amélie (Canadian French). You can only change the narrator by changing the device language.

Above you can get a glimpse of the issue. If you have your phone in a language other than the language that you are reading, your phone will try to narrate that to you in a random language. Sometimes its the article language, mostly it’s not. I know that it is irresponsible to say “random” since there are usually around only two choices, so basically, you’re flipping a coin each time you try to narrate text with your device. Take the situation I mentioned earlier with Montreal: you can get a feel for the linguistic situation by checking out the sub-reddit. It’s a completely bilingual environment. If you need Screen Speak for any reason, your device is incompatible with /r/montreal. If you can only have your device in one language, that puts a barrier to your understanding of texts of interest that might come across your reading list: government documents, local news, world news and novels.

This isn’t a difficult problem to solve from a computer science perspective. Language recognition scripts have been effective since the 90s and Apple already has word-level parsing for their bilingual typing feature. It wouldn’t be any problem at all for a subroutine to “pre-read” the text on the screen, check which language dominates and then force the TTS system to use that language. Alternatively, they could create a swipe gesture to toggle the language currently being used for narration or have a 3d-touch mechanism for toggling between the different languages. The macOS approach is that the language menu is stuffed away in System Preferences under Accessibility under the heading “Voice”. This method is not ideal but at least it allows you to have one language for your system and another for your TTS narrator. There are a lot of ways to tackle this issue, but I wish that Apple would just choose one.

I first contacted Apple about this on July 16, 2014 (rdar) during the iOS 8 beta. Apple got in touch with me for follow-up regarding the bug. I detailed the issue extensively and created a test project where the issue was reproducible. Since then, I have gotten in touch with them on numerous occasions filing additional bug reports after major OS updates. I also got in touch with them through their new accessibility e-mail address accessibility@apple.com. I also got in touch with Apple employees via Twitter. I also filed an Apple Technical Support Incident request, of which developers are permitted two per year with their annual $99 membership. I don’t want to place the blame on Tim Cook, but it is his Apple that has stunted the progress of this necessary feature. This article represents the last tick in a checklist of things that are in my power to bring about awareness and change in this problem.

To summarize, this is a real problem affecting many people, but the number isn’t important. People who can’t read for one reason or another don’t have an option to go somewhere else. They can’t just switch to Android. They can’t just consume all monolingual media. Apple needs to continue to work to make sure that their accessibility functions work for everyone. We all know that Apple will respond to the public. I really hope that you can consider sharing this article so that the right person at Apple might read it and help bring this feature to everyone.